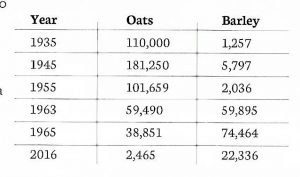

Oats/Corn

One of the greatest changes in farming over the last sixty years is the enormous decline in the acreage of oats (or corn, as oats referred to locally) and a corresponding increase in the amount of land under barley. As can be seen from the table above, comparing the figures for 1935 and 1945 the Second World War had a dramatic influence on the area of tillage. The production of both crops declined over the next ten years and there was marked decrease generally in the amount of cereals being grown (down from 191,057 ha to 105, 917 ha) but oats was still by far the most popular crop. However, it is interesting to see that by 1963 both oats and barley were produced in almost equal amounts (59,490 Ha and 59,895 Ha), and after that the balance altered completely. By 1965, the output of barley was almost double that for oats. Cultivation of both crops steadily declined in the intervening years, reflecting the overall move away from tillage.

The main reason for the transformation is the virtual disappearance of the horse from the farm and the arrival of the combine harvester.

As Harry Armstrong explains:

barley wasn’t grown in the 1950s, just oats then with the coming of the combine everything changed: ……barley didn’t really come in until the combine came. Then we started to grow barley and it just changed over completely. There was no oats after that, it was all barley……the oats didn’t combine well. You had to keep it till it was too ripe and then it used to be ‘strow-broken’ ………before it was ready for combining so barley took over.

And Raymond Mcnamee describes how the variety of corn he remembers being used, Stormont Sceptre, was no longer suitable for present-day methods:

The Sceptre wouldn’t really have been a corn for nowadays because it grew to be at least six feet high and nowadays it’s the short stuff they want because it’s the actual seed that they want off it. There was a problem………that if you got a bad night’s wind the whole thing went down flat to the ground and it was a nuisance to try to cut. It was a job for the scythe and sharpening stone then.

Up until the 1960s oats were grown on all the farms taking part in the survey. Shiels at Crewe House grew four to five acres, Armstrongs at Parkhill Farm grew twelve acres, James Armour’s father grew twelve acres as well. Raymond McNamee remembers his father growing ……… While Charlie Convery’s grandfather could have grown five acres, Charlie himself grew up to fifteen acres.

Once the ground was ploughed and prepared, the seed was sown with the aid of a corn fiddle then fertilizer spread. Children were drafted in when necessary, James Armour remembers helping his father:

Michael McNamee driving, Willlie Turner ‘tilting’ (laying off)

If it was a busy time and the weather was going to be good we may have got the great opportunity of being allowed stay off school if we were going to carry the corn to my father……it was great to get off the school but it wasn’t so great when you had to carry buckets of corn through a field of deep soil and you were about eight or nine – just old enough to be able to lift the bucket of corn high enough to empty it into the hopper of the old corn fiddle . I didn’t enjoy that. I would go into a daydream sitting there on the bag of corn and my father would give a gulder; ‘where are you? I need another bucket.’ As the crop grew, so did the weeds, and James spent long hours as a child manually removing the dockens and thistles with a thistling tool which was ‘almost the same size as myself’.

(l-r) Raymond McNamee, Willie Turner & Michael McNamee

During the ‘40s and ‘50s the crop was cut by either a reaper or binder, but the scythe was not totally redundant, Harry describes his father ‘opening-up’ the field before cutting the crop:

My father would have been a lot tidier than me. When mowing the oats he always cut a path around the field with a scythe so that the horses did not walk over the oats the first time round the field.

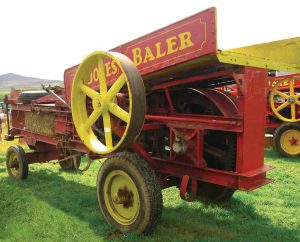

We were all (James with Uel and Maurice, his brothers), vying for the job to drive the tractor to bring the huts into the thresher………then shoot back down the field at a very high speed on the tractor with the buckrake to bring in another hut. At ten or eleven year’s old it was a great day’s work…….threading the baler was a dreaded job……Freddie Cauldwell always did it with one helper and too often that helper was me… My mother was the centre-piece of the whole thing. Food was very important to the working man……fourteen men could come into the kitchen for their dinner……as a showing of respect coming into any house a man would never sit at the table with his cap on. They always took it off and put it behind them on the chair. (James Armour)

We were all (James with Uel and Maurice, his brothers), vying for the job to drive the tractor to bring the huts into the thresher………then shoot back down the field at a very high speed on the tractor with the buckrake to bring in another hut. At ten or eleven year’s old it was a great day’s work…….threading the baler was a dreaded job……Freddie Cauldwell always did it with one helper and too often that helper was me… My mother was the centre-piece of the whole thing. Food was very important to the working man……fourteen men could come into the kitchen for their dinner……as a showing of respect coming into any house a man would never sit at the table with his cap on. They always took it off and put it behind them on the chair. (James Armour)

Several contractors operated in the area at the time:

At that time the thresher man was Jakie Sufferin and before him was Freddie Caldwell. Atty McLean out the road was another threshing contractor He would have come to us for a day and then he would have moved down the road to another farmer, so really all farmers in the area knew when the thresher was in the area. (Raymond McNamee)

…….Robert Hugh Dripps, then the Heuston brothers took over. Robert Hugh had a birthday not so long ago. I think it was his 96th (Harry Armstrong)

There were a number of thresher men in the area, Freddie Caldwell, Robert Hugh Dripps, Joe Johnston, Jakie Sufferin and Atty McLean. Freddie Caldwell was the one I remember coming to our Farm, a big tall powerful person who in my eyes could do anything. (James Armour)

Charlie Convery recalls another contractor too, Dan Convery who was known as Dan the Navy.

After threshing the corn was used to feed the stock and for bedding:

……..the straw would have been used for bedding and sometimes we might have used it with fodder with a taste of treacle or something put over it. The corn itself would have been kept and brought to my Grandfather’s mill for, we called it bruising – it’s actually crushing and you’d have fed that to the cattle. If it was good clean corn …….you’d maybe have kept a few bags for next year’s sowing. You sowed, I think they used to talk of about eight stones to the acre. (Raymond McNamee)

Raymond’s brother, Michael McNamee, with several of his friends who were also vintage enthusiasts like himself, made a film, based on 1955 illustrating the complete season of the corn harvest.

The making of the film ‘Farming down the Years’ was the brainchild of my late brother Michael. This was a film he wanted to make and show to future generations, so he asked me for the field and I agreed. He then got in touch with his friends and neighbours namely; Tommy Doherty, Willie Turner, Paddy McKenna etc. The film took over a year to make taking all the various stages into consideration. Michael died a short time after its completion……. John Thompson thought it looked so well he marketed it with much success. This was the first farming video to be made (locally) and the start of a trend.

Still available, this film gives an insight into the work practices of the mid-fifties and was a significant contribution to capturing the essence of harvest time in a different era.